Osgood-Schlatter Disease

What You Need to Know

- Osgood-Schlatter disease is a common cause of knee pain in young children and adolescents who are still growing.

- Most children will develop Osgood-Schlatter disease in one knee only, but some will develop it in both.

- Athletic young people are most commonly affected by Osgood-Schlatter disease—particularly boys between the ages of 10 and 15 who play games or sports that include frequent running and jumping.

- Treatment for Osgood-Schlatter disease includes reducing the activity that makes it worse, icing the painful area, using kneepads or a patellar tendon strap, and anti-inflammatory medication.

- Surgery is rarely used to treat Osgood-Schlatter disease.

What is Osgood-Schlatter disease?

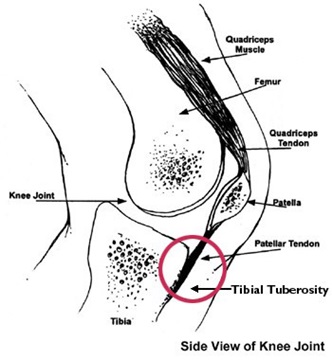

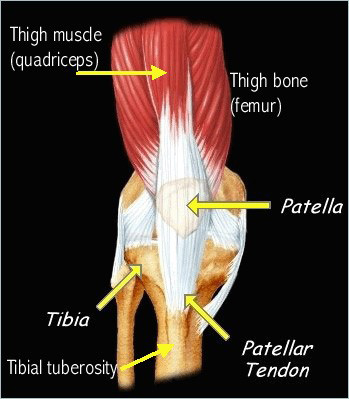

Osgood-Schlatter disease is a condition that causes pain and swelling below the knee joint, where the patellar tendon attaches to the top of the shinbone (tibia), a spot called the tibial tuberosity. There may also be inflammation of the patellar tendon, which stretches over the kneecap.

Osgood-Schlatter disease is most commonly found in young athletes who play sports that require a lot of jumping and/or running.

What causes Osgood-Schlatter disease?

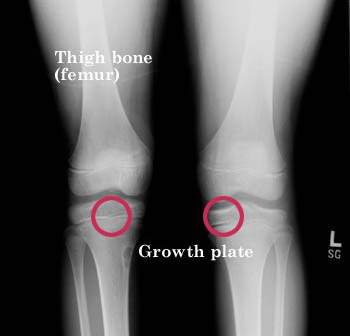

Osgood-Schlatter disease is caused by irritation of the bone growth plate. Bones do not grow in the middle, but at the ends near the joint, in an area called the growth plate. While a child is still growing, these areas of growth are made of cartilage instead of bone. The cartilage is never as strong as the bone, so high levels of stress can cause the growth plate to begin to hurt and swell.

The tendon from the kneecap (patella) attaches down to the growth plate in the front of the leg bone (tibia). The thigh muscles (quadriceps) attach to the patella, and when they pull on the patella, this puts tension on the patellar tendon. The patellar tendon then pulls on the tibia, in the area of the growth plate. Any movements that cause repeated extension of the leg can lead to tenderness at the point where the patellar tendon attaches to the top of the tibia. Activities that put stress on the knee—especially squatting, bending or running uphill (or stadium steps)—cause the tissue around the growth plate to hurt and swell. It also hurts to hit or bump the tender area. Kneeling can be very painful.

How is Osgood-Schlatter disease treated?

Osgood-Schlatter disease usually goes away with time and rest. Sports activities that require running, jumping or other deep knee-bending should be limited until the tenderness and swelling subside. Kneepads can be used by athletes who participate in sports where the knee might make contact with the playing surface or other players. Some athletes find wearing a patellar tendon strap below the kneecap can help decrease the pull on the tibial tubercle. Ice packs after activity are helpful, and ice can be applied two to three times a day, 20 to 30 minutes at a time, if necessary. The appropriate time to return to sports will be based on the athlete’s pain tolerance. An athlete will not be “damaging” his or her knee by playing with some pain.

Your doctor may also recommend stretching exercises to increase flexibility in the front and back of the thigh (quadriceps and hamstring muscles). This can be achieved either through home exercises or formal physical therapy.

Medicine, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—like ibuprofen (Aleve and Advil)—can be used to help control pain. If your child needs multiple doses of medication daily and the pain affects their daily activities, there should be a discussion on resting from the sport.

Is surgery ever needed for Osgood-Schlatter disease?

In almost every case, surgery is not needed. This is because the cartilage growth plate eventually stops its growth and fills in with bone when the child stops growing. The bone is stronger than cartilage and less prone to irritation. The pain and swelling go away because there is no new growth plate to be injured. Pain linked to Osgood-Schlatter disease almost always ends when an adolescent stops growing.

In rare cases, the pain persists after the bones have stopped growing. Surgery is recommended only if there are bone fragments that did not heal. Surgery is never done on a growing athlete, since the growth plate can be damaged.

If pain and swelling persist despite treatment, the athlete should be re-examined by a doctor regularly. If the swelling continues to increase, the patient should be re-evaluated.